Madang Timbers Ltd v Matthew & Othrs [2024]

Supreme Court decision referring the question of damages for reassessment in an employment dispute

Logging companies mentioned in this document:

SC2749

PAPUA NEW GUINEA

[SUPREME COURT OF JUSTICE]

SCA NO. 31 OF 2024

BETWEEN

MADANG TIMBERS LIMITED

Appellant

AND

SONNY MATTHEW FOR AND ON BEHALF OF HIMSELF AND

PETER JAI, JERRY GANZ, MATTHEW AMBONG, ARNOLD

ARUMBAI, THADDEUS MARK, MICHAEL AURIP, GOMIA KIMIN,

GEORGE KAMBIN, LUKE SAI, AND EKI MUNAME

Respondents

WAIGANI: COLLIER J, CARMODY J, CROWLEY J

26 JUNE, 4 JULY 2025

CONSTITUTION – s. 41 “proscribed acts” - not a “guaranteed right or

freedom” for the purposes of ss 57 and 58. Breach of s. 41 – no entitlement to

damages as compensation under s. 58. S. 58(1) is an addition to, and not in

derogation of, s. 57.

EMPLOYMENT LAW – Inherent power imbalance

DAMAGES – An exercise of judicial discretion – nominal damages.

Brief Facts

The appellant employed each of the respondents as security guards and paid

them at a rate of K2.70 per hour as compensation prior to 2014. Sometime in

2014 the appellant changed the respondents’ remuneration to a fixed rate of

K450 per fortnight. The respondents, under significant pressure, signed

individual contracts containing the new fixed rate of pay but were not made

aware of the new rate.

In 2018 the respondents sought assistance form the Provincial Labour Office in

Madang to improve their employment terms including the change in the rate of

pay which they said they had not been informed of at the time of the execution

of the contracts. The Labour Office and the appellant then entered into a series

of communications. In 2019 the respondents’ employment was either terminated or they were not re-employed by the appellant. The respondents instituted Court proceedings against the appellant and were successful on the issue of liability at the National Court. The judgment with respect to damages included damages pursuant to s. 58 of the Constitution and nominal damages. The appellant appealed the judgment on assessment of damages. HELD: 1. A breach of s. 41 of the Constitution is not capable of remedy through s. 57 of the Constitution. 2. The primary Judge, in conducting an assessment of damages, did not consider irrelevant facts, or facts not supported by evidence. Cases cited Breckwoldt & Co. (N.G.) Pty Ltd v Groyke [1974] PNGLR 106 Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v OS MCAP Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 51 Curtain Brothers (PNG) Ltd v UPNG [2005] SC758 Kaluwin v Haiveta [2023] SC2384 Nimbituo v Commissioner of the Correctional Service [2025] SC2729 Paraia v The State (1995) N1343 Premdas v Independent State of Papua New Guinea [1979] PNGLR 329. Raz v Matane [1985] PNGLR 329 SCR No 1 of 1984; Re Minimum Penalties Legislation [1984] PNGLR 314 Counsel Mr T Injia for the Appellant Mr S Gor for the Respondents

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

BY THE COURT: Before the Court is an appeal from a decision of a Judge of

the National Court of Papua New Guinea in Matthew v Ling [2024] PGNC 34;

N10687 (primary Judgment). The primary Judgment concerned an assessment

of damages owed to the respondent by the appellant (Madang Timbers Limited).

The matter before the primary Judge concerned the appellant’s liability to pay

damages to the respondents, and subsequently the quantity of such damages,

arising out of the employment of the respondents by the appellant. The appellant

appeals the primary Judge’s findings that, in summary, the respondents were

entitled to damages under s 58 of the Constitution for breach of s 41 of the

Constitution, and that there was sufficient evidence for the calculation of

nominal damages. The first and second defendants to the proceedings below are

not party to this appeal – the corporate entity is the sole appellant.

The appellant relies on four grounds of appeal, namely:

(1) The National Court erred in law and mixed fact and law by

applying the principles established in Petrus v Telikom PNG

Limited (2008) N3373 which was followed in David Simon v

Michael Koisen (2018) N7075, Pama v Chris Gens (trading as

Kanagio Security Services) (2020) N8516, Bual v Kila (2021)

N9329 and awarding compensation for breach of s.41 of the

Constitution in addition to damages for unlawful termination

and in so doing departed from the principles established in

Jimmy Malai v Papua New Guinea Teachers Association [1992]

PNGLR 568 and New Britain Oil Limited v Sukuramu (2008)

SC946 that it is an employer's right to hire and fire and the

measure of damages for unlawful termination was an

employee's notice period and his outstanding wages and

entitlements under his employment contract and the

Employment Act and nothing further.

(2) The National Court erred in law or mixed fact and law by

ruling that the respondents were entitled to compensation under

section 58 (3) of the Constitution pursuant to the National

Court's power under section 57 of the Constitution for a breach

of section 41 of the Constitution in that the Supreme Court in

Raz v Matane (1985) PNGLR 329 established that section 41 of

the Constitution did not create a basic right enforceable by

section 57 of the Constitution.

(3) The National Court erred in law or mixed fact and law in

that it should have found that in all circumstances, including the

evidence of the respondents, the power imbalance between the

respondents was not relevant in assessing damages for unlawful

termination as the respondents' claim in the National Court was

for unpaid entitlements, wages and over time between 2015 and

2019 and not for the entire duration of their employment with

the appellant, and that in all circumstances the National Court

could not be satisfied that it was reasonable to award higher

compensation than a nominal amount of K2,000 awarded in

comparative cases where a breach of section 41 of the

Constitution was established such as Peter Pama v Chris Gens

(2020) N8516 and Simon v Koisen (2018) N7075, and in Petrus

v Telikom (2008) N3373.

(4) The National Court erred in law and mixed fact and law by

taking into consideration the fact that all of the respondents had

been employed by the appellant for most of their working lives

and one of the respondent was employed since 1999, a fact not

supported by the evidence, in that those facts were not relevant

for assessing damages for unpaid wages and entitlements and

by so doing awarded an amount greater than the nominal

amount of K2,000 awarded in comparative cases such as Peter

Pama v Chris Gens (2020) N8516 and Simon v Koisen (2018)

N7075, and in Petrus v Telikom (2008) N3373.

In our view, the appeal should be allowed. We have formed this view for the

reasons that follow.

background

At all relevant times, the appellant employed each of the respondents as security

guards.

Prior to July 2014, the respondents were all paid a salary of around K2.70 per

hour as compensation for their services as security guards.

In or about July 2014, the appellant transferred the respondents’ renumeration to

a fixed rate of K450 per fortnight. It is not in contention that the respondents all

signed individual contracts agreeing to that new fixed rate. The primary Judge

found that the respondents were under significant pressure when they signed the

new contract and were not aware of its provisions.

In 2018, the respondents contacted the Provincial Labour Officer in Madang

(Mr Peter Neimani) to seek assistance with improving their employment terms.

Thereafter, throughout 2018 and 2019, a series of correspondence was sent

between the Labour Office and the appellant. Several meetings were also held.

In 2019, the respondents’ employment was either terminated, or they were not

re-employed by the appellant.

Primary Judge’s decisions

On 30 November 2020, the primary Judge published judgment in Matthew v

Ling [2020] PGNC 406; N8665 (the Liability Judgment). Importantly, that

judgment was not appealed, and is not the subject of this appeal.

On 15 March 2024, the primary Judgment was delivered.

On the issue of the principles of assessing a quantum of damages, his Honour

held, relevantly:

13.Breach of s 41(1) of the Constitution in an employer/employee

situation has attracted compensatory damages under the

Constitution in this jurisdiction, and the court adopts this approach

in this case Petrus v Telikom PNG Ltd (2008) N3373, cited with

approval in Morobe Provincial Government v Kameku (2012)

SC1164.

14.Addressing now the question of quantum of damages for breach of

s 41, under s 58(3) of the Constitution, my findings at paragraphs

27 to 31 in my decision on liability (Matthew v Ling (2020)

N8665) is the common thread in the evidence of the plaintiffs that

led me to conclude that the plaintiffs’ rights under s 41(1)(a),(b)

and (c) of the Constitution were breached. Mr Wak relies on the

case of Kolokol v Ambuarapi (2009) N3571 to argue that quite

apart from compensatory damages for breach of human rights, a

human rights victim is entitled to general damages. In a number of

cases such as Buat v Kila (2021) N9329 I have taken this approach.

Breach of s 41 of the Constitution in an employer/employee

situation has attracted damages in the range of K2,000. In Pama v

Chris Gens (trading as Kanagio Security Services) (2020) N8516 I

awarded K2,000 for breach of s 41(1) of the Constitution and

K2,000 general damages.

In applying the above principles, his Honour found, relevantly:

15. Due to the power imbalance between the employer

and employee in this situation, and the lengthy service

of the plaintiffs, warrants a higher award than Pama v

Gens. In Petrus v Telikom PNG Ltd (2008) N3373, K5,000 was awarded in circumstances where the security guard were employed for more than four years. The plaintiffs in this case, have spent much of their working life with the defendants. I will therefore award K10,000 to each plaintiff for breach of their rights. I do not think that it is appropriate to award a specific sum for general damages as I have dismissed the claim for negligence. I also accept the defendants’ submissions that the plaintiffs had a duty to mitigate their losses. There is also evidence that most of them continue to occupy the defendants’ premises at no cost. The wife of one of the deceased plaintiffs, is now in the employ of the third defendant. Mitigation in this instance, meant that they were required to seek employment elsewhere to reduce their loss. 16. In relation to the claim for final entitlements, one of the crucial documents which the plaintiffs relied on to prove the loss of entitlement was a letter dated 17 May 2021from Hubert Laboi from the Madang office of the Department of Labour. I referred to this piece of evidence earlier in my judgement. The defendants objected to the tendering of that document because the plaintiff could not have the author of the letter available for cross examination, and the letter was attached to the affidavits of the plaintiffs. I upheld that objection. Without the author of the letter, the defendants are denied the opportunity to cross-examine the witness and the court cannot verify the claim. How then do I quantify the plaintiffs’ loss of entitlements, given the absence of verified claims? 17. In Jonathan Mangope Paraia v The State (1995) N1343, Injia J (as he then was) held that the fact that damages cannot be assessed with certainty does not relieve the wrongdoer of the necessity of paying damages. Where precise evidence is available the court expects to have it. However, where it is not, the court must do the best it can. I take this approach in this case which I followed in Tai v Aka (2020) N8618. 18. From my general knowledge, the usual items that are factored into any final entitlements are the annual leave entitlements, the notice period, plus any unpaid overtime. The evidence is that the plaintiffs have not been paid these entitlements which I found on the

question of liability. The predicament is that there is no

exact sum from the evidence. From the final

entitlements that the defendants have calculated, the

figures range from K1,761.12 to K2,638.88. This was

for the 2019 year alone (Jeffrey Ling’s affidavit). From

the plaintiffs’ affidavits, one of them commenced

employment as far back as 1999 and all of them were

in employment for much of their life with the third

defendant. I take these into account and award a

nominal sum to each of the plaintiff of K10,000.00.

Given their lack of evidence to verify the quantum

although they have established a cause of action for

unpaid entitlements, the amount I have assessed is

reasonable.

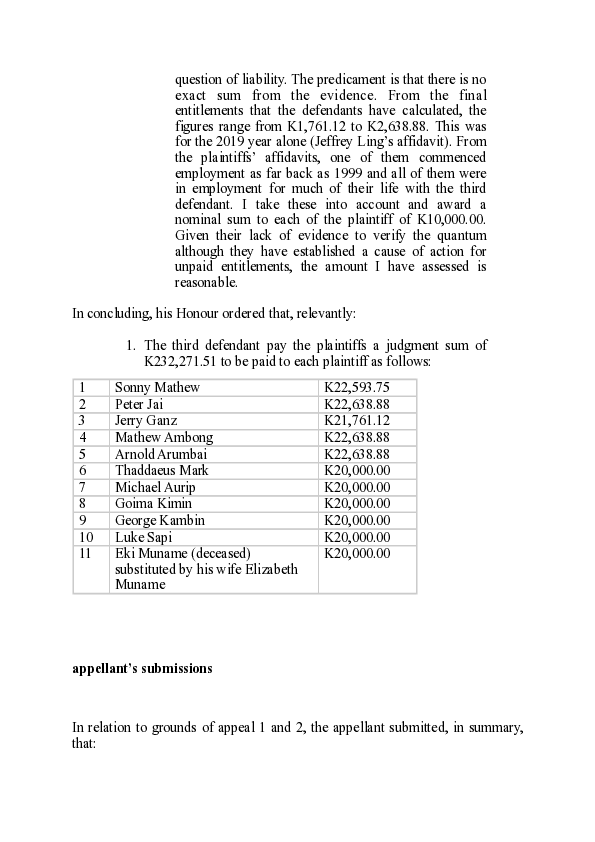

In concluding, his Honour ordered that, relevantly:

1. The third defendant pay the plaintiffs a judgment sum of

K232,271.51 to be paid to each plaintiff as follows:

1 Sonny Mathew K22,593.75

2 Peter Jai K22,638.88

3 Jerry Ganz K21,761.12

4 Mathew Ambong K22,638.88

5 Arnold Arumbai K22,638.88

6 Thaddaeus Mark K20,000.00

7 Michael Aurip K20,000.00

8 Goima Kimin K20,000.00

9 George Kambin K20,000.00

10 Luke Sapi K20,000.00

11 Eki Muname (deceased) K20,000.00

substituted by his wife Elizabeth

Muname

appellant’s submissions

In relation to grounds of appeal 1 and 2, the appellant submitted, in summary,

that:

• The respondents filed 30 affidavits in the proceedings below which were

objected to by the appellant. The primary Judge upheld the appellant’s

objections to those affidavits and ruled them inadmissible. The

respondents relied on only the appellant’s affidavit of Jeffrey Ling filed 4

October 2019, and the facts established in the Liability Judgment.

• At trial, the respondents sought damages under four separate heads. The

appellant submitted that the Primary Judge should have only awarded

damages as compensation for the loss of the respondents’ entitlements.

• Despite a lack of pleadings and evidence by the respondents at trial, the

primary Judge followed the rulings in Petrus v Telikom Limited (2008)

N3373 and other cases along the same line of authority, and awarded

damages for a breach of s 41 of the Constitution.

• The primary Judge fell into error by relying on irrelevant or erroneous

authorities from the National Court, which were contrary to binding

Supreme Court authority. Instead, the primary Judge should have relied

on this Court’s ruling in Kaluwin v Haivetta [2023] SC2384.

• The primary Judge fell into error by awarding damages for the breach of s

41 of the Constitution, departing from principles of binding authority

that:

• private employers have the right to hire and fire at will (in the

absence of express agreement to the contrary): Jimmy Malai v

PNGTA [1992] PNGLR 567; New Britain Oil Limited v Sukuramu

(2008) SC946; and

• the measure of damages for unlawful termination is what an

employee would have received for his salary and other

entitlements, had his employment been lawfully terminated:

Porgera Joint Venture Manager Placer (PNG) Ltd v Robin Kami

(2010) SC1060 at [15], [21] and [24].

• For these reasons, the primary Judge’s award of K10,000 to each

respondent in compensation for the appellant’s breach of s 41 of the

Constitution, should be quashed.

In relation to grounds of appeal 3 and 4, the appellant submitted, in summary,

that:

• At [12] of the primary Judgment, his Honour considered facts not in

evidence, and facts that were irrelevant to the exercise of discretion for a

claim of final entitlements. Specifically, there was no evidence that any of

the respondents was employed continuously since 1999, or that the

respondents had worked for the appellant for much of their lives.

• The primary Judge failed to consider the principles established in

Ruhuwamo v PNG Ports Corporation Limited (2019) N8021 at [21] and

in PNGBC v Jeff Tole (2002) SC694. In PNGBC, Kandakasi J established

that where a plaintiff’s claim for damages is special in nature, it must be

specifically pleaded with particulars.

• The respondents failed to plead their loss of wages and entitlements and

did not produce any evidence at the trial, including evidence which would

allow for a nominal award higher than made in comparable cases.

respondents’ submissions

In relation to grounds 1 and 2, the respondents submitted, in summary, that:

• The appellant never appealed the Liability Judgment and is barred from

raising any findings of that judgment in this appeal.

• It is trite law that a breach of s 41 of the Constitution can give rise to a

cause of action.

• The respondents’ claims before the primary Judge were not for wrongful

termination. Rather, the claims were for damages based on the appellant’s

actions towards the respondents throughout the course of the respondents’

employment.

• In cases such as Petrus, the National Court awarded compensation for a

breach of s 41 of the Constitution. By following such cases, the primary

Judge did not fall into error.

• The primary Judge was aware that compensation for a breach of s 41

could not be awarded under s 57, and made the deliberate choice to award

compensation under s 58 instead.

In relation to grounds 3 and 4, the respondents submitted, in summary, that:

• Most of the evidence of the respondents regarding their terms of

employment with the appellant was uncontroversial. The evidence of the

appellant by its affidavit of Jerry Ling did not rebut the respondents’

evidence regarding the terms of their employment. In this respect, the

primary Judge found that the facts led by the respondents were cogent,

credible and corroborated: Liability Judgment at [26].

• The primary Judge summarised the actions of the appellant which led to

the conclusion that the appellant had breached s 41 of the Constitution at

[27] to [32] of the Liability Judgment.

• In calculating the final entitlements of the respondents, the primary Judge

relied on the evidence of the appellant in the affidavit of Mr Ling. This

figure was reasonable.

• The cases relied on by the appellant in relation to comparative awards of

damages were delivered years before.

• In Petrus, the National Court awarded each plaintiff K11,147.96.

• In the circumstances, the primary Judge’s award of damages was not

attended by error.

consideration

At the hearing, it emerged that there were essentially three key issues before the

Court, being:

(1) whether compensation can be awarded as a result of a breach of s 41 of

the Constitution;

(2) whether the primary Judge’s award of nominal damages was excessive as

it was made without evidence; and

(3) whether the Court could properly award compensation to the respondents

for the same injury, under two different heads of damages.

We will consider each of these issues in turn below.

Whether Compensation can be Awarded as a Result of a Breach of s 41 of

the Constitution

Section 41 of the Constitution provides:

41. Proscribed acts.

(1) Notwithstanding anything to the contrary in any other

provision of any law, any act that is done under a valid law

but in the particular case—

(a) is harsh or oppressive; or

(b) is not warranted by, or is disproportionate to, the

requirements of the particular circumstances or of the

particular case; or

(c) is otherwise not, in the particular circumstances,

reasonably justifiable in a democratic society having a

proper regard for the rights and dignity of mankind,

is an unlawful act.

(2) The burden of showing that Subsection (1)(a), (b) or (c)

applies in respect of an act is on the party alleging it, and

may be discharged on the balance of probabilities.

(3) Nothing in this section affects the operation of any other law

under which an act may be held to be unlawful or invalid.

As already noted, the primary Judge, in the Liability Judgment, found that the

appellant had breached s 41. In the primary Judgment, his Honour then awarded

compensation under s 58(3) of the Constitution for said breach.

Section 58 of the Constitution provides, relevantly:

58. Compensation.

(1) This section is in addition to, and not in derogation of,

Section 57 (enforcement of guaranteed rights and

freedoms).

(2) A person whose rights or freedoms declared or protected by

this Division are infringed (including any infringement

caused by a derogation of the restrictions specified in Part

X.5 (internment)) on the use of emergency powers in

relation to internment is entitled to reasonable damages and,

if the court thinks it proper, exemplary damages in respect of

the infringement.

(3) Subject to Subsections (4) and (5), damages may be awarded

against any person who committed, or was responsible for,

the infringement.

...

(emphasis added)

At the hearing, Counsel for the appellant submitted that s 58 does not operate

independently of s 57 of the Constitution, and the two must be considered

together, at least in the context of this matter.

Section 57 of the Constitution provides, relevantly:

57. Enforcement of guaranteed rights and freedoms.

(1) A right or freedom referred to in this Division shall be

protected by, and is enforceable in, the Supreme Court or the

National Court or any other court prescribed for the purpose

by an Act of the Parliament, either on its own initiative or on

application by any person who has an interest in its

protection and enforcement, or in the case of a person who

is, in the opinion of the court, unable fully and freely to

exercise his rights under this section by a person acting on

his behalf, whether or not by his authority.

...

(emphasis added)

The key issue before the Court in this respect is whether

In Raz v Matane [1985] PNGLR 329, Kapi DCJ explained:

I am not persuaded that s 41 confers a “right or freedom”. The

provision deals with acts that are empowered to be done or are

allowed to be done by a valid law. The provision sets out the

circumstances, (s 41 (a), (b) or (c)), under which such acts may be

held unlawful of invalid. The whole thrust of the provision is

directed at these actions. It does not confer a “right or freedom” as

for example “right” to privacy under s 49 or “freedom” of

assembly and association under s 47.

However, any person aggrieved by acts which are prohibited by s

41 (a), (b) or (c), may seek judicial remedy in terms of the

provision. That is to say, he has a cause or right of action upon

which he may make an application to a court. McDermott J

expressed this well when discussing s 41 in the Minimum Penalty

case, (at 363):

‘... As well there is the newer remedy in the form of a

declaratory order available, provision for which is made in

the National Court Rules. But, the difficulty has always been

in getting a cause of action if you like to establish the basis

on which to bring one of these actions. Access to courts has

been fairly limited in this area. I consider s 41 wittingly or

unwittingly remedies that – it supplies a right of action....’

Such a cause of action arises or is constituted at the time these

actions are taken.

In this sense, a person has a right of action to come to the Court.

This is quite a different thing from a “right or freedom” referred to

in the Constitution, s 57.

In Raz, Kidu CJ, with whom Kapi DCJ agreed, found:

There is, in my opinion, no doubt that s 41 of the Constitution

confers a right – the right to challenge an act done under a valid

law. In SCR No 1 of 1984; Re Minimum Penalties Legislation

[1984] PNGLR 314 the following was said by Kapi DCJ at

332-333 of the nature of this right:

‘... A remedy under s 41 cannot be described as an

enforcement of a right or freedom under s 57 of the

Constitution, and therefore the National Court has no power

to grant the remedy. It is a general remedy which is quite

distinct and separate from enforcement of a right or

freedom ...

Section 57 can have no application to the issue in question.

Section 57 only applies to enforcement of rights or

freedoms. As I have already pointed out, s 41 is a separate

and distinct constitutional remedy.’

His Honour the Chief Justice then went on to conclude that:

There is absolutely no doubt that s 41 does not provide for a

human right.

Section 57 was quite clearly meant to be used by the Supreme

Court, the National Court and any other court designated by an Act

of the Parliament to remedy breaches of human rights.

...

(emphasis added)

Prior to Raz, this Court reached a similar conclusion in Premdas v Independent

State of Papua New Guinea [1979] PNGLR 329.

In Kaluwin v Haiveta [2023] SC2384, this Court adopted the approaches of the

Court in Raz and Premdas. In a unanimous decision, detailing the authorities

concerning, and principles underpinning ss 41 and 57, their Honours concluded:

...we find the decisions and the respective reasoning in each of the

cases are sound and should be maintained. We adopt the reasoning

in those decisions as our own. Proceeding on that basis, we are of

the view that s. 41 does not create and or grant a right capable of

enforcement under s. 57 of the Constitution.

... Plainly, the law is settled that a breach of s 41 is not capable of remedy through s 57 of the Constitution. We respectfully adopt the reasoning of the Supreme Court in the above authorities. At the hearing, the respondent sought to distinguish the above line of authority on the basis that the trial Judge in this instance exercised his Honour’s power under s 58 of the Constitution, not s 57. We find that there is no basis for such distinction. According to the authorities above, the reason for the inapplicability of s 57 to remedy a breach of s 41 is that s 41 does not create a “right or freedom” for the purposes of s 57. Similarly to s 57, s 58 is clearly predicated on being used to remedy a right or freedom: s 58(2) of the Constitution. Without the breach of a “right or freedom” the ability to rely on s 58 is not enlivened. Further, s 58(1) states that it “is an addition to, and not in derogation of, Section 57 (enforcement of guaranteed rights and freedoms)”. It follows that there is no basis whatsoever for distinguishing the ability to remedy a breach of s 41 with the use of s 57 or s 58. Sections 57 and 58 can be distinguished, for example, from s 23 of the Constitution. That section allows for the awarding of compensation by the National Court for acts not limited to a “guaranteed right or freedom”. In light of the above, the primary Judge had no proper basis for ordering damages to be paid pursuant to s 58 of the Constitution for breach of s 41 of the Constitution. It follows that ground of appeal 2 is substantiated. At the hearing, the appellant relied on grounds of appeal 1 and 2 largely as a combined ground. Given our finding in relation to ground 2, there is no utility in ground 1, and it therefore need not be considered. Whether the Primary Judge’s Award of Nominal Damages was Attended by Error It is well settled that the assessment of damages involves an exercise of judicial discretion : see for example Nimbituo v Commissioner of the Correctional Service [2025] SC2729 at [12]-[14]. It is also settled law that this Court – when considering an appeal from a lower Court’s exercise of discretion in awarding damages – will only disturb such an order if the discretion was exercised in accordance with a wrong principle, or where the lower Court relied on

extraneous or irrelevant material, mistook the facts, or failed to consider

relevant facts: see, e.g., Curtain Brothers (PNG) Ltd v UPNG [2005] SC758 at

12, citing Breckwoldt & Co. (N.G.) Pty Ltd v Groyke [1974] PNGLR 106 at

112-113.

Principles relevant to an assessment of damages were clearly laid out by the

primary Judge at [5] of the primary Judgment. The appellant has raised no

appeal from the identification of the relevant principles by the primary Judge.

By ground 3, the appellant’s only challenge to the primary Judgment is that the

primary Judge relied on extraneous or irrelevant material, or mistook the facts,

in assessing damages.

The appellant submits that the primary Judge’s consideration of a “power

imbalance” between the appellant and the respondents was not supported by

evidence. The appellant further submits that a consideration of any power

imbalance was erroneous as the respondents’ claim was merely for unpaid

entitlements between 2015 and 2019.

At [26] of the Liability Judgment, his Honour found:

27. I find the facts led by the plaintiffs to be cogent, credible and

corroborated. The evidence shows that the manner the

plaintiffs were treated were harsh and oppressive...

The primary Judge continued:

27. The defendants’ actions to pay the plaintiffs a fixed salary of

K450 per fortnight from when it commenced in 2014 to

2019 was to avoid paying the plaintiffs for actual hours

worked...

It can be readily inferred that the primary Judge’s recognition of a power

imbalance between the appellant and the respondents in assessing damages,

followed the unchallenged factual findings of the primary Judge in the Liability

Judgment. In particular, the fact that the appellant was able to avoid paying its

employees their minimum legal entitlements for a period of at least 5 years.

In any event, in the vast majority of cases, there will be an inherent power

imbalance between an employer and its employees. The Full Court of the

Federal Court of Australia has similarly recognised that such a power imbalance

is “inherent”: Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v OS

MCAP Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 51 at [38].

In OS MCAP, the Full Court held:

38. ...the provision confronts is the inherent power imbalance

that exists between employers and employees. By virtue of

this imbalance, employees will often feel compelled, and not

understand, that they have the capacity to refuse a request

that is unreasonable or where their own refusal is reasonable.

We are not persuaded that the primary Judge fell into error by considering that

there was a power imbalance between the appellant and the respondents in

assessing damages payable to the respondents.

By ground 4, the appellant again claims that the primary Judge relied on

extraneous or irrelevant material, or mistook the facts in assessing damages.

This ground takes issue with the alleged excessive nature of the damages

awarded.

The appellant submits that the primary Judge erred by taking into consideration

the fact that all of the respondents had been employed by the appellant for

substantial periods of time. The appellant submits that this consideration was

irrelevant and not supported by evidence.

The assertion that many of the respondents had been employed for significant

periods of time was noted by the primary Judge at [9] of the Liability Judgment.

That observation was followed by the primary Judge’s finding that the

respondents’ assertions of fact were “cogent, credible and corroborated” at [26]

of the Liability Judgment.

As we have already stated, the Liability Judgment, including the primary

Judge’s findings of fact therein, are not the subject of this appeal. Therefore, for

this Court to consider the correctness of such findings would be an exercise of

judicial power outside the jurisdiction of this Court.

In light of the above, we find that the primary Judge, in conducting the

assessment of damages, did not consider irrelevant facts, or facts not supported

by evidence.

For completeness, the appellant submitted that the respondents were only

entitled to their unpaid entitlements on termination, and accordingly, any award

should be limited to K2,000 for each respondent. The problem with this

submission is threefold.

First, the appellant’s case was not merely one for wrongful termination. The

claim was a broad one relating to the appellant’s conditions of employment and

renumeration over an extended period of time. As we observed earlier, the

appellant’s claim and prayer for relief in its Statement of Claim was phrased

extremely broadly.

Second, the primary Judge noted at [5] of the primary Judgment that there was insufficient evidence for an exact award of nominal damages to be reached. Instead, his Honour correctly relied on Paraia v The State (1995) N1343 in stating that it is the Court’s task to do the best it can with the evidence before it. That is what the primary Judge did. The primary Judge’s task was particularly difficult in that the appellant’s liability included a failure to pay the respondents overtime for an extended period. Precisely calculating such entitlements was a near impossible task. The task of this Court is not to determine whether we would have awarded the same amount of damages as the primary Judge. The task of this Court is to identify whether there was any error in the primary Judge’s approach. There was no such error. Third, the appellant’s claim that each respondent should be awarded K2,000 in damages is entirely inconsistent with both its submissions before this Court, and those before the primary Judge. Counsel for the appellant in this Court submitted that there should be clear evidence to calculate damages. The appellant provided no such calculation for the award of damages it seeks in this appeal. Also, before the primary Judge, the appellant submitted that the total award of damages should be K73,000. The appellant has provided no explanation for the substantial difference in the orders it seeks from this Court, as compared to those sought before the primary Judge. As we observed earlier in these reasons, the appellant did not raise any issue with the primary Judge’s identification of principles of assessment of damages. The appeal from the assessment of nominal damages was limited solely to the appellant’s claims about the consideration by the primary Judge of particular facts. We have found that there was no such error on the part of the primary Judge. As such, grounds of appeal 3 and 4 are not substantiated. conclusion Each party has enjoyed some success in this appeal. In the circumstances, we consider it appropriate for each party to bear their own costs of the appeal. We now turn to the appropriate form of orders to give effect to these reasons. The respondents’ Statement of Claim filed 13 August 2019 made a broad claim as to damages sought. It is clear, from the transcript of the hearing on assessment of damages before his Honour, that the appellant did not argue that the National Court lacked power to award compensation for a breach of s 41 of the Constitution. Plainly the appellant’s case in this Court was substantially different to that argued before the primary Judge.

We consider that, had the primary Judge correctly found that the National Court

did not have the power to award compensation for a breach of s 41, his Honour

may have made a different award of damages.

Accordingly, we consider it appropriate that the matter be remitted to the

primary Judge for a fresh consideration of the assessment of damages.

63. The Court orders that:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. The matter be remitted to the primary Judge for a directions hearing

whereby timetabling orders are made for the parties to file any further

evidence on the assessment of damages.

3. The primary Judge reassess the damages in light of the reasons of this

Court and any further evidence filed pursuant to timetabling orders

made in accordance with para 2 of these Orders.

4. There be no order as to costs.

________________________________________________________________

Lawyers for the appellant: Ashurst

Lawyers for the respondents: Gor Lawyers as Town Agent for Bradley & Co

Lawyers