Two steps forward, two steps back: the mobilisation of customary land in Papua New Guinea

Logging companies mentioned in this document:

Concessions mentioned in this document:

Two steps forward, two steps back:

the mobilisation of customary land in

Papua New Guinea

Colin Filer

Abstract

In May 2019, the Minister for Lands convened a National Land Summit in Port

Moresby to review the implementation of the National Land Development

Program over the course of the past decade. Much of the discussion at this meeting

was concerned with the incorporation of customary land groups and the voluntary

registration of their collective land titles under legislation that was passed by the

National Parliament in 2009 but did not take effect until 2012. Participants in the

summit thought that the implementation of this legislation had not proven to be

an effective way of ‘mobilising customary land for development’. This paper seeks

to explain why the new legal and institutional regime has failed to live up to the

expectations of the policymakers who were instrumental in its establishment. An

initial examination of the rationale behind the legislation is followed by an

examination of published evidence relating to its implementation in different

parts of the country, including case studies of areas where the evidence serves to

illuminate the motivations of the actors involved in the process of incorporation

and registration. The paper concludes with some reflections on the lessons to be

learnt from this experiment in policy reform.

Discussion Paper 86

December 2019

Series ISSN 2206-303X

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

Two steps forward, two steps back: the mobilisation of customary

land in Papua New Guinea

Colin Filer

Colin Filer1 is an Honorary Professor at the Crawford School of

Public Policy, The Australian National University.

Filer, C. 2019. “Two Steps Forward, Two Steps Back: The Mobilisation of

Customary Land in Papua New Guinea”. Development Policy Centre

Discussion Paper #86, Crawford School of Public Policy, The

Australian National University, Canberra.

The Development Policy Centre is a research unit at the Crawford

School of Public Policy, The Australian National University. The

discussion paper series is intended to facilitate academic and

policy discussion. Use and dissemination of this discussion paper

is encouraged; however, reproduced copies may not be used for

commercial purposes.

The views expressed in discussion papers are those of the author

and should not be attributed to any organisation with which the

author might be affiliated.

For more information on the Development Policy Centre, visit

http://devpolicy.anu.edu.au/

1 This paper is dedicated to the memory of my old friend Lawrence Kalinoe, former head of PNG’s

Constitutional and Law Reform Commission and then Secretary for Justice, who sadly passed

away during the public consultations that led to the 2019 National Land Summit. I thank Jim

Fingleton, Siobhan McDonnell and Jason Roberts for their comments on earlier drafts of this

paper. Other individuals cited in the text have provided bits of information that have enabled me

to get somewhat closer to the truth of what has gone on in particular parts of PNG. None of these

commentators or informants are responsible for any factual errors that remain, let alone for my

interpretation of the evidence.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

Contents

1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. 1

2. Problems with the old regime............................................................................................................................... 2

3. The new regime in theory .....................................................................................................................................10

3.1 Steps in the land group incorporation process ................................................................................................ 11

3.2 Steps in the title registration process ................................................................................................................... 13

4. New anomalies in the National Gazette ...........................................................................................................15

5. An elastic deadline and the shape of novelty ................................................................................................23

6. The end of the lease-leaseback scheme ..........................................................................................................30

7. Leaseholders lost and found ................................................................................................................................32

7.1 Leaseholding land groups in rural areas ............................................................................................................. 32

7.2 Leaseholding land groups in urban and peri-urban areas.......................................................................... 35

8. Roselaw and Tubumaga ........................................................................................................................................37

9. Recycled agro-forestry projects .........................................................................................................................40

9.1 Vailala Oil Palm Project ................................................................................................................................................ 40

9.2 Aitape West Integrated Agriculture Project....................................................................................................... 41

9.3 Urasirk Rural Development Project ....................................................................................................................... 44

10. Unprecedented rural clumps ..............................................................................................................................45

10.1 Torokina Oil Palm Development Project ............................................................................................................ 46

10.2 The Lavongai leases ...................................................................................................................................................... 48

10.3 Lak Kandas Oil Palm Project..................................................................................................................................... 52

10.4 Idam Siawi Agro-Forestry Project ......................................................................................................................... 54

11. The growth of urban bias ......................................................................................................................................59

11.1 Land groups under a peri-urban local-level government .......................................................................... 60

11.2 Land groups under the Poreporena–Napa Napa Development Plan .................................................... 66

11.3 Ohobidudare transformations ................................................................................................................................. 72

12. Discussion and conclusion ...................................................................................................................................75

13. References ..................................................................................................................................................................85

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

Two steps forward, two steps back: the mobilisation of customary

land in Papua New Guinea

1. Introduction

In May 2019, a three-day National Land Summit held in Port Moresby identified 17 issues

relating to the ‘efficient utilisation of customary land for the benefit ... of the customary

landowners’ and adopted a resolution on each one of them. Among these were resolutions

calling for a review of the existing legal and institutional regime that regulates the

processes of land group incorporation and voluntary customary land registration (GPNG

2019). The participants had evidently come to the conclusion that this was not proving to

be an effective way of ‘mobilising customary land for development’.

The current legal and institutional regime is the result of a policy process initiated by a

previous national land summit held in 2005 (GPNG 2007; Yala 2010). Its central feature

is a set of amendments to the Land Groups Incorporation Act 1974 and the Land

Registration Act 1981 that were passed by the National Parliament in 2009 but did not

come into effect until 2012. These amendments created an opportunity for incorporated

land groups (ILGs) to register collective land titles once they had met new standards of

transparency and accountability in the process of incorporation. Groups that had already

been incorporated under the original legislation were given five years in which to

reincorporate themselves under the amended legislation, whether or not they were

seeking to register titles to their land, and were threatened with extinction if they failed

to do so.

During the three years that elapsed between the passage and certification of the new

legislation, the national government established a commission of inquiry into the grant

of what the Land Act of 1996 calls ‘special agricultural and business leases’ (SABLs). This

was part of a separate policy process (Filer 2017), but the topic under investigation was

a peculiar institution that was created to compensate for the inability of incorporated

land groups to register collective land titles under the old legal regime. Although the

government put a stop to the grant of such leases when the inquiry was established in

2011, there remains a good deal of uncertainty about the legal status of the leases that

1

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

had already been granted (Filer and Numapo 2017). Furthermore, the perceived failure

of the new legislation to produce the desired level of ‘land mobilisation’ has caused the

participants in the latest land summit to call for a ‘review [of] the relevance of the SABL

process within the context of the land tenure reforms’ (GPNG 2019).

This paper seeks to explain why the new legal and institutional regime has failed to live

up to the expectations of the policymakers who were instrumental in its establishment.

Section 2 asks why they thought that it would solve the problems inherent in the old

regime and thus create new opportunities and incentives for the ‘mobilisation’ of

customary land. Section 3 then examines the way in which their reasoning was reflected

in the specific provisions of the amended legislation. Section 4 shows how notices

published in the government’s National Gazette since 2013 highlight the failure of the

Department of Lands and Physical Planning to implement some of these provisions.

Section 5 deals with some of the reasons why so many land groups that were

incorporated under the old legal regime have not yet been reincorporated under the new

one, and why the government has therefore extended the window of opportunity that

was meant to close in 2017. Sections 6 to 9 deal with the relationship between the

suspension of the SABL scheme in 2011 and the introduction of the new voluntary

customary land registration scheme in 2012, with a number of case studies used to

illustrate the complexity of this relationship. Sections 10 and 11 then use additional case

study material to illustrate what is known about the motivations of people who have

taken advantage of the opportunities offered by the new legal regime, and how these

motivations might vary between rural and urban areas. The concluding section returns

to the issues posed by the resolutions of the latest national land summit, specifically to

the question of what explains the perceived failure of the policy experiment initiated by

the legislation of 2009 and what, if anything, might now be done to produce a more

successful version of this experiment.

2. Problems with the old regime

In a sense, the recent amendments made to the Land Groups Incorporation Act and Land

Registration Act do not mark the beginning of a new policy regime but the completion of

a national policy process that began with the recommendations of the Commission of

Inquiry into Land Matters back in 1973 (GPNG 1973; Ward 1983). The original Land

2

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

Groups Incorporation Act of 1974 was one of several pieces of legislation that were meant

to implement these recommendations, but it held a central place in the whole package

because incorporated land groups were seen as a prime example of what is meant by the

fifth goal of the National Constitution, which is ‘to achieve development primarily through

the use of Papua New Guinean forms of social, political and economic organisation’

(Fingleton 1982). In this case, the assumption was that all the indigenous citizens of the

newly independent state were members of customary groups that were also ‘land groups’

because they were the collective owners of all customary land, and the custom of each

group was what decided the allocation of use rights to the individual members (Power

2008). The Act did not use words like ‘clan’ or ‘tribe’ to describe these customary groups,

nor did it make any assumption about the nature of the customary rules that they applied

to the allocation of use rights. It simply required that each group should formulate a

constitution before it could be granted legal recognition by the state. The Registrar of

Incorporated Land Groups could require additional information, including a list of the

group’s members, but this was optional. He or she could also refuse to recognise a group

that did not appear to qualify as a ‘customary land-owning group’, but had to provide

reasons for such a decision.

A standard application form was attached to the Act. This could be filled in and signed by

any number of people claiming to be members of the land group, and only had to specify

the name of the group, the local-level government area in which its land was located, and

the identity of the proposed ‘dispute-settlement authority’. The latter could consist of a

number of individuals, or the occupants of specific positions, who were empowered by

the group’s constitution to settle disputes between its members. The constitution also

had to specify the qualifications for membership of the group itself and the body set up

to manage its affairs. The Act outlined a process by which the registrar was obliged to

advertise the existence of each application, circulate copies to interested parties for any

comments or objections, and then advertise a subsequent decision to recognise the group

in question. Once incorporated, a land group could apply to the registrar to change its

constitution, and such applications were to be treated in the same way as applications for

incorporation. A group could also be wound up or dissolved, either at its own request or

on the basis of a recommendation to the registrar from a village court or district court, if

there were problems in the management of its affairs.

3

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

Section 1 of the Land Groups Incorporation Act noted that the process of land group

incorporation was not only meant to facilitate the more effective use of customary land

and the resolution of disputes about its ownership, but also to create ‘greater certainty of

title’. The Act made no provision for land groups to register titles to their land because

this additional step was understood to be one that would need a separate piece of

legislation (Bredmeyer 1975). Although the commission of inquiry had recommended

that such a law be drafted, this did not happen. The resulting hole in the legal framework

was filled by a stopgap measure that has come to be known as the ‘lease-leaseback

scheme’. Under this scheme, incorporated land groups could lease their land to the state

so that the state could create a registered title over it and then lease it back to the land

groups themselves, or else to what are known in PNG as ‘landowner companies’, in which

land groups should ideally be the shareholders. This scheme was originally devised in the

late 1970s (Hulme 1983), and was later given formal recognition through a set of

amendments made to the Land Act in 1996 (Filer 2011a).

The primary source of information about the actual incorporation of land groups under

this legal regime consists of a long sequence of ‘notices of lodgement of an application for

recognition as an ILG’ that were published in the National Gazette between 1992 and

2012. These application notices normally assigned a number to each of the land groups

seeking recognition. The highest number known to have been allocated in this way is

17988. One might therefore suppose, as many people do, that a total of almost 18,000

land groups had applied for recognition by 2012. However, this appears to be an

overestimate.

The first application notice was published in October 1992, shortly after the function of

land group recognition was transferred from the Registrar of Companies to the

Department of Lands and Physical Planning. In November 1993, the Registrar of

Incorporated Land Groups published a notice in the National Gazette listing 140 land

groups that had already been granted certificates of recognition, of which 80 had been

recognised before the end of January 1993, and 17 before the end of 1991, without ever

having their application notices gazetted. The numbers assigned to these 80 groups

ranged from 6 to 223, which indicates that 143 numbers had already gone missing, in the

sense of not being ‘owned’ by any recognised group. The one application notice published

at the end of 1992 was followed by 13,576 unique application notices between 1993 and

4

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

2012.2 This suggests that a lot more land group numbers went missing during that period,

for reasons that are still unclear (Antonio et al. 2010). Although there are some cases,

within that period, in which certificates of recognition have been issued to land groups

whose applications for incorporation were not gazetted, the number appears to be much

smaller than the number of numbers that were not assigned to any group. I am therefore

inclined to think that the total number of applicants was more likely to be 15,000 than

18,000.

In 2011, the Registrar of Incorporated Land Groups implied that applications for

incorporation were almost invariably successful before he was appointed to the position

in 2010, mainly because they were only advertised in the National Gazette, and not in the

national newspapers that have a much wider circulation (Rogakila 2011). It is not

possible to verify this assertion from evidence contained in the gazette, because

application notices were very rarely followed by notices of recognition until 2011, despite

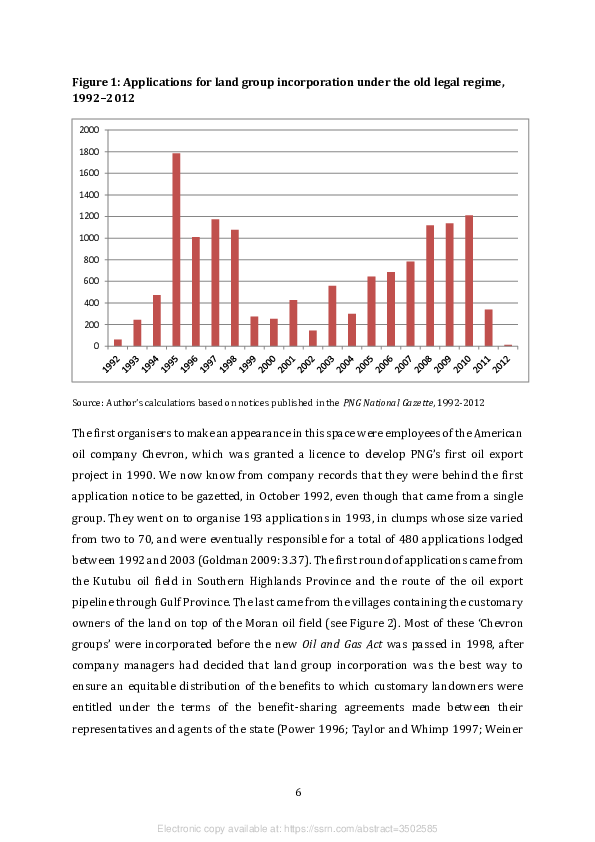

the requirements of the Act. Figure 1 shows that the number of applications that were

gazetted reached a peak in the years between 1995 and 1998, and then peaked again in

the years between 2008 and 2010. To explain this ‘double hump’, we need to consider the

additional sources of evidence that lead to an explanation of the motives behind the

applications. The motives are most easily discovered when several applications were

listed in a single notice, or when multiple applications from the same area were gazetted

on the same day, albeit in separate notices. This kind of ‘clumping’ betrays the presence

of an organiser who is not a member of any of the groups being incorporated yet has a

vested interest in the result.

2 I have discounted a number of cases in which an application notice was accidentally gazetted twice

within a month. However, I have come across some cases, one of which is mentioned towards the end of

this paper, in which the same group seems to have had an application notice gazetted on more than one

occasion at greater intervals of time. I have not been able to eliminate such instances of duplication

from my dataset because I have only recorded the names of the land groups, as well as the number

making applications from particular villages, in a few parts of the country that were selected for more

intensive study.

5

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

Figure 1: Applications for land group incorporation under the old legal regime,

1992–2012

2000

1800

1600

1400

1200

1000

800

600

400

200

0

Source: Author’s calculations based on notices published in the PNG National Gazette, 1992-2012

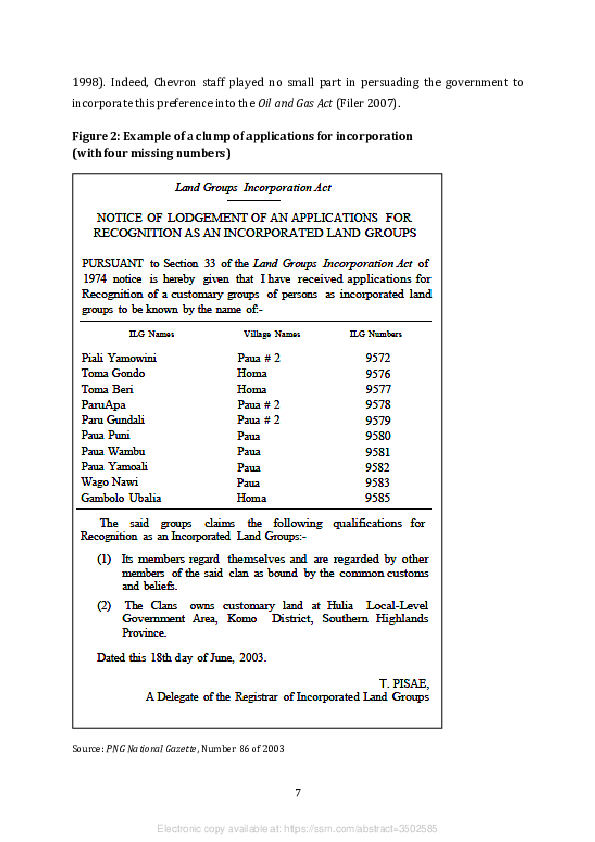

The first organisers to make an appearance in this space were employees of the American

oil company Chevron, which was granted a licence to develop PNG’s first oil export

project in 1990. We now know from company records that they were behind the first

application notice to be gazetted, in October 1992, even though that came from a single

group. They went on to organise 193 applications in 1993, in clumps whose size varied

from two to 70, and were eventually responsible for a total of 480 applications lodged

between 1992 and 2003 (Goldman 2009: 3.37). The first round of applications came from

the Kutubu oil field in Southern Highlands Province and the route of the oil export

pipeline through Gulf Province. The last came from the villages containing the customary

owners of the land on top of the Moran oil field (see Figure 2). Most of these ‘Chevron

groups’ were incorporated before the new Oil and Gas Act was passed in 1998, after

company managers had decided that land group incorporation was the best way to

ensure an equitable distribution of the benefits to which customary landowners were

entitled under the terms of the benefit-sharing agreements made between their

representatives and agents of the state (Power 1996; Taylor and Whimp 1997; Weiner

6

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

1998). Indeed, Chevron staff played no small part in persuading the government to

incorporate this preference into the Oil and Gas Act (Filer 2007).

Figure 2: Example of a clump of applications for incorporation

(with four missing numbers)

Source: PNG National Gazette, Number 86 of 2003

7

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

Most of the land group incorporation that took place in the second half of the 1990s had

nothing to do with Chevron, but stemmed from a preference expressed in Section 57 of

the Forestry Act of 1991. This treated the process of incorporation as a mechanism for

securing the free, prior and informed consent of customary landowners to a forest

management agreement (FMA) by which their timber harvesting rights would be

transferred to the state before being allocated to a logging company (Filer 2007). The first

clump of applications associated with this mechanism was a group of 45 from West New

Britain Province in July 1994, but the first of these agreements to be signed was a set of

three that covered the Turama Extension concession in Gulf Province, which is the biggest

single logging concession in PNG. A total of 331 applications from this area were gazetted

between October 1994 and June 1995, nearly all of them towards the end of this period

and some after the agreements had been signed in May that year. Many of the clumps of

applications associated with FMAs are easily identified because the notices in the

National Gazette declare that the relevant clans own land in a designated ‘timber area’ or

‘forest area’, rather than assigning them to a local government area, as is the normal

practice. According to a draft update of the National Forest Plan prepared in 2012 (GPNG

2012), around 5.8 million hectares of land had been covered by FMAs signed between

1995 and 2010, but most of the agreements were signed between 1995 and 1998.3

Officials in the new National Forest Service were trained in the practice of land group

incorporation by consultants working on the Forest Management and Planning Project,

which was funded by the World Bank between 1993 and 1998 as part of the wider

program of forest policy reform (FMPP 1995). One of the consultants previously

responsible for organising the Chevron groups produced a ‘Village Guide to Land Group

Incorporation’ (Power 1995) that recommended the production of property lists,

genealogies, and other forms of evidence that were not formally required by the

legislation, but were meant to convince the registrar that the groups were genuine. Copies

of this manual appear to have circulated beyond the boundaries of areas earmarked for

3 For various reasons, some of the clumps of applications associated with designated ‘timber areas’ or

‘forest areas’ did not lead to FMAs, and even when they did, some of the agreements had been set aside by

2012, either because they had not been properly formulated or because of disputes amongst the

landowners whose groups had been incorporated (Forest Trends 2006; Bird et al. 2007).

8

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

FMAs, and might have been responsible for some clumps of applications that were neither

organised by Chevron staff nor facilitated by forestry officers.

The second peak in the number of applications, between 2008 and 2010, was due to a

rapid increase in the size of the SABLs being granted to landowner companies or their

‘development partners’ under the terms of the lease-leaseback scheme. Public concern

over the scale of this form of alienation is what led to the establishment of the commission

of inquiry in 2011. The commission’s mandate was to investigate 74 of the leases to find

out whether they had been granted with ‘prior consent and approval’ by the customary

landowners (Filer 2017). The commissioners found that such consent had been absent in

most cases, which cast doubt on the authenticity of the land groups through which their

consent had supposedly been secured. However, the policy process that led to the

termination of the lease-leaseback scheme in 2013 had no effect on the policy process

that led to the amendment of the Land Groups Incorporation Act and Land Registration

Act, since the latter process had begun with a land summit convened in 2005 and ended

when the amendments were drafted in 2008, before the lease-leaseback scheme became

a major political issue (GPNG 2007, 2008; Yala 2010).

What initially sparked concern about the proliferation of ‘bogus’ land groups was the

publication of a notice in the National Gazette, in April 1999, ‘dissolving and cancelling’

the registration of 25 of the Chevron groups that had been counted as owners of the land

on top of the Kutubu oil field. It transpired that this was the work of the former governor

of Southern Highlands Province, whose own power base was located in the vicinity of the

oil field, and who was sponsoring the incorporation of another collection of land groups

with a view to diverting part of the benefit stream into his own pocket or the pockets of

his supporters. While Chevron staff managed to persuade the Lands Department to

reinstate the registration of their 25 groups in 2001, the number of alternative land

groups with claims to belong to the project area continued to proliferate. About 550 of

these groups were incorporated between 1993 and 2010. By the end of this period, they

had been joined by as many as 250 groups whose clumping betrayed an intention to claim

landowner benefits from the gas fields that have now been added to the existing oil fields

as components of PNG’s first liquefied natural gas project. To the best of my knowledge,

only eight of these 800 groups was sponsored or organised by the developers (Goldman

2007: 112), so the other organisers are most likely to have been local ‘big men’, possibly

9

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

acting in concert with officials from the Department of Petroleum and Energy (Koyama

2004; Weiner 2007).

A second source of concern was an SABL over 50,000 hectares of land that was granted

to the Piu land group in 2001. This area surrounded a prospective mining project in

Morobe Province, and the beneficiaries, who had lodged their application for

incorporation in 1995, were representatives of a single village who were seeking to

exclude other villages from the prospective benefits (Filer 2011a: 274). This case was not

investigated by the subsequent commission of inquiry, partly because the lease had been

granted to a land group rather than a private company, but also because it had already

been the subject of a protracted legal dispute between representatives of the different

villages in the area. By the time of the land summit in 2005, the lease had already been

revoked by the lands minister, his decision had been quashed by the National Court, but

then upheld by the Supreme Court, officers of the Lands Department had been made to

look rather stupid, and the whole contest had been aired at some length in the national

newspapers (Anon. 2004, 2005a, 2005b; Krau 2005). Instead of taking this as a reason to

question the utility of the lease-leaseback scheme, members of the National Land

Development Taskforce took it as evidence of the need to amend the Land Registration

Act so that land groups could get land titles in another way (GPNG 2007).

3. The new regime in theory

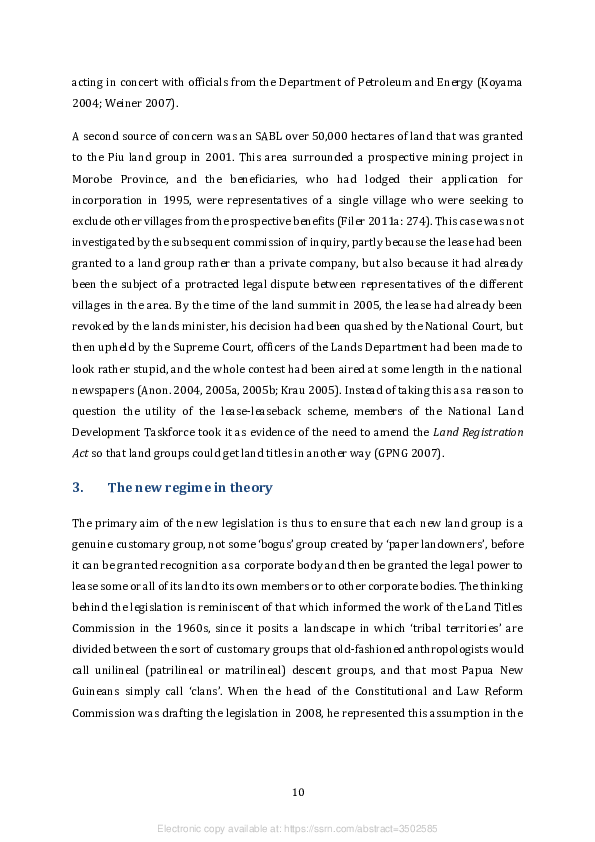

The primary aim of the new legislation is thus to ensure that each new land group is a

genuine customary group, not some ‘bogus’ group created by ‘paper landowners’, before

it can be granted recognition as a corporate body and then be granted the legal power to

lease some or all of its land to its own members or to other corporate bodies. The thinking

behind the legislation is reminiscent of that which informed the work of the Land Titles

Commission in the 1960s, since it posits a landscape in which ‘tribal territories’ are

divided between the sort of customary groups that old-fashioned anthropologists would

call unilineal (patrilineal or matrilineal) descent groups, and that most Papua New

Guineans simply call ‘clans’. When the head of the Constitutional and Law Reform

Commission was drafting the legislation in 2008, he represented this assumption in the

10

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

form of a diagram in which a tribal territory is divided between four clan territories, and

one of the four clans ‘mobilises’ a rectangular portion of its own territory by registering

a title over it (see Figure 3). If we imagine that a ‘tribe’ is roughly the same size as a local

council ward, and each one is divided into four ‘clans’, then the average size of each clan

estate — at least in rural areas — would be about 2,000 hectares.

Figure 3: Division of land group properties imagined by the Constitutional and

Law Reform Commission

Source: GPNG 2008: 40

3.1 Steps in the land group incorporation process

The most significant innovation in the amended version of the Land Groups Incorporation

Act is a far more detailed set of instructions about the ‘prescribed material’ to be provided

to the Registrar of Incorporated Land Groups in an application for incorporation. The

First Schedule of the Act says that the applicants must provide a ‘true and complete’ list

of the group’s members, accompanied by (a) evidence of their qualification to be

members of the group, (b) evidence that they are not members of any other land group,

11

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

and (c) certified copies of their birth certificates.4 They must also provide a list of the

group’s property, including a description of the land area over which the group claims

customary rights. The Second Schedule says that this must specify the boundaries of the

area in the form of a sketch map, and should include evidence of any boundary disputes

with neighbouring groups (see Figure 3).

If the registrar is satisfied that the application complies with the provisions of the Act,

Section 5 requires that a notice of lodgement of the application be published in the

National Gazette. Copies of this notice must also be sent ‘to the district administrator in

whose area the land group or any of the property claimed on behalf of the land group is

situated’ and to the ‘village court within whose jurisdiction members of the group reside’.

They in turn are required to disseminate the notice ‘in such manner they think most likely

to ensure that it is widely known to person[s] having knowledge of or an interest in the

affairs of the land group or its members’. The applicants should not receive a certificate

of recognition until the registrar knows that this has been done.

The amended Act has not done much to clarify what should be done in the event of

objections being made to the incorporation of a new land group. It makes no reference to

the possible role of village courts or local land courts in dealing with such objections.

Section 5 only deals with those objections that can be construed as ‘internal disputes

relating to the identity of the group’s representatives, officers or membership’. In such

cases, the registrar can either reject the application or do nothing until it appears that the

dispute has been resolved.

The amended Act retains the provisions previously made for land groups to change their

constitutions or to be wound up or dissolved, but it also contains new requirements for

evidence that they are being properly managed. Section 14 requires each land group to

hold a general meeting within three months of registration, and thereafter at intervals of

one year, attended by at least 60 per cent of the group’s members. It also requires the

management committee to notify the registrar of any changes to its own composition and

to provide a statement of the group’s assets and liabilities at regular intervals. Section 28

4 It is not clear how the registrar would know whether individuals were being listed as members of more

than one group in the absence of a database capable of comparing the birth certificates of the members of

different land groups. Even that would not be a reliable source of information if people can obtain more

than one birth certificate under different names.

12

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

allows the registrar to seek additional information about the operation or membership

of each registered land group, and grants any member of the public access to the

information contained in a group’s file.

3.2 Steps in the title registration process

The amended Land Registration Act states that the representatives of a recognised land

group may apply to the Director of Customary Land Registration (‘the director’) to

register their ownership of, or interest in, an area of customary land. There is no

requirement that a land group apply to register all of the land over which it claims

ownership, but nor is there any limit on the proportion of the group’s land that can be

subject to the process of registration.

The requirements of this process are mainly set out in Section 34 of the amended Act.

This says that an application must be accompanied by a ‘registration plan’ that must

include a description of the boundaries of the ‘land or parcels of land’ that are ‘absolutely’

owned by the applicants. The Act does not say what counts as a ‘description’ for this

purpose, but it seems to consist of a combination of two documents that have long been

part of the procedures for the acquisition of customary land by the state — a land

investigation report and a survey plan. These need to be part of a registration plan in

order to produce what Section 34K calls a ‘good root of title’. The application for

registration may also contain, ‘where necessary’, the names of people who are not

members of the group but who still have ‘derivative interests’ in this area of land,

‘including the boundaries of the parcels of such land and the nature of the interest’.

On receipt of the application, the director is required to verify the membership of the land

group and the boundaries of the parcels of land described in the registration plan. This

should entail a meeting with members of the group and a physical inspection of the

boundaries to be undertaken in the company of the group’s ‘appointed representatives’.

This requirement invokes the practice that has been known since colonial times as

‘walking the boundaries’. Once this verification exercise has been completed, the director

is required to produce a version of the registration plan that includes any consequential

revisions or amendments. This is understood to be a further opportunity to include

people who have ‘derivative interests’ in the area.

13

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

The director is then required to forward a copy of the registration plan to the Regional

Surveyor and at the same time advertise the existence of the plan ‘in such a manner he

considers appropriate to bring it to the attention of all persons who may have an interest

in the land or parcels of land’ covered by the plan. The regional surveyor would normally

be a suitably qualified officer of the Lands Department based in the province or region

where the land is located. His or her job is to check whether the registration plan includes

any land that is already subject to a title granted by the state, and if so, to produce an

‘adjusted registration plan’ that resolves this inconsistency. The advertisement is meant

to be published in the National Gazette and the national newspapers, just like notices of

applications for land group incorporation. In this case, the notice should inform people

where the registration plan can be examined and how they can make an objection to it

within a period of ‘not more than 90 days’. People objecting to a plan are required to state

whether they do so in a personal capacity or as the representative of a ‘customary group’.

Objections are apparently to be dealt with at the discretion of the director. As in the case

of the amended Land Groups Incorporation Act, the amended Land Registration Act makes

no reference to the possible role of village courts, land mediators or local land courts in

the settlement of disputes between the people making the application and the people

objecting to it. Once the period allowed for objections has expired, and any objections

received during that period have been dealt with, the director is required to prepare a

‘final registration plan’ that forms the basis of advice to the Registrar of Titles to issue a

certificate of title to the land group. The legislation does not seem to require the director

to publish a notice to the effect that this has been done.

Once a land group has been registered as an ‘owner of clan land’, it has the power to grant

‘derivative rights and interests’, typically in the form of leases, to itself, or to any of its

members, or to any other entity. Leases to itself or its members do not seem to require

government approval, but leases to other entities are treated as ‘controlled dealings’,

which means that they need to be registered.

There is no legal mechanism by which the land in question can then be separated from its

collective owner. The land ceases to be subject to ‘customary law’ except insofar as

custom still applies to the transmission of rights to be members of the group holding the

title (Chand 2017). In effect, this means that the group will already have alienated a

14

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

portion of its own land to itself, and will thus have become the customary owner of what

is no longer customary land, even if it is still ‘clan land’. At the same time, the customary

group will also have alienated part of its own identity, because the ‘clan’ will have turned

into something that looks and behaves like a miniature version of a private company.

4. New anomalies in the National Gazette

To assess the manner in which the new legislation has been implemented, I have

compiled a spreadsheet based on information contained in the notices published in the

National Gazette since the legislation came into effect in 2012. There are five main types

of notice, each of which has a distinctive official title that I have abbreviated for the

purpose of the present discussion (see Table 1).

Table 1: Standard notices gazetted under the new legal regime

FULL TITLE ABBREVIATION

Notice of lodgement of an application for recognition as an ILG Application notice

Notice of grant of certification of recognition Recognition notice

Notice of invitation for objection under Section 34G Survey notice

Notice of intention to accept land investigation report Acceptance notice

Notice of registered survey plan Land title notice

Application notices almost invariably identify the name of the proposed land group with

that of the ‘clan’ to which its members are said to belong. They also name the village or

villages where the group’s members are resident and the local-level government (LLG)

area, the district and the province in which they are located. The notices generally include

a list of the vernacular names of the ‘properties’ or land assets claimed by the group, but

the length of this list varies a lot from one notice to another.

Recognition notices assign a number to the group that is about to be recognised. These

notices state that a group has ‘complied with the traditional customs’ of the village

previously named in the application notice, and list the names of the individuals

nominated as members of its management committee and dispute settlement authority.

The management committee is normally said to comprise six individuals — a

15

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

chairperson, deputy chairperson, secretary, treasurer and two female representatives.

The dispute settlement authority is commonly said to comprise three individuals, each of

whom is assigned to a village that may or may not be the same as the village in which the

group is based, and each of whom is also assigned a status such as ‘village elder’, ‘land

mediator’ or ‘village court magistrate’.

Survey notices provide the customary name and estimated area (in hectares) of the land

portion or portions over which a land group is proposing to conduct a ‘land investigation’

and a ‘survey’. These notices invite interested parties to lodge any objections to the

group’s existing ‘sketch’ of this territory within a period of 30 days, and state that copies

of the sketch can be viewed in the offices of the (national) Director of Customary Land

Registration, the Provincial Lands Advisor, or the Regional Surveyor. In some cases, the

notices already assign a number to the proposed survey plan.

Acceptance notices purport to advise ‘customary landowners’ within the relevant LLG

area that the Director of Customary Land Registration is in receipt of a land investigation

report for the portion or portions of land claimed by a land group, and invite any

‘aggrieved’ landowners who share a ‘common boundary’ to register their approval or

objection within a period of 30 days. These notices assign portion numbers as well as

survey plan numbers to the land parcels that have been investigated.

Land title notices state that the Director of Customary Land Registration, in consultation

with the Surveyor General, has accepted the land group’s survey plan as the basis for

registration of its ‘customary land title’ over the land parcels to which portion numbers

have already been assigned in the acceptance notices.

Application notices and recognition notices have occasionally been amended because of

changes in the list of land assets claimed by a land group or changes in the composition

of its management committee or dispute settlement authority. In 2018, there were also

four notices to advise that a land group had been ‘wound up’ because it was found to be

16

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

illegitimate, but only one of the four groups had previously been subject to a recognition

notice as well as an application notice. 5

Specific notices are sometimes repeated, presumably by accident, in different issues of

the gazette, but such instances of duplication have been discounted in my calculation of

the number of notices published between 2013 and 2018 (Table 2).

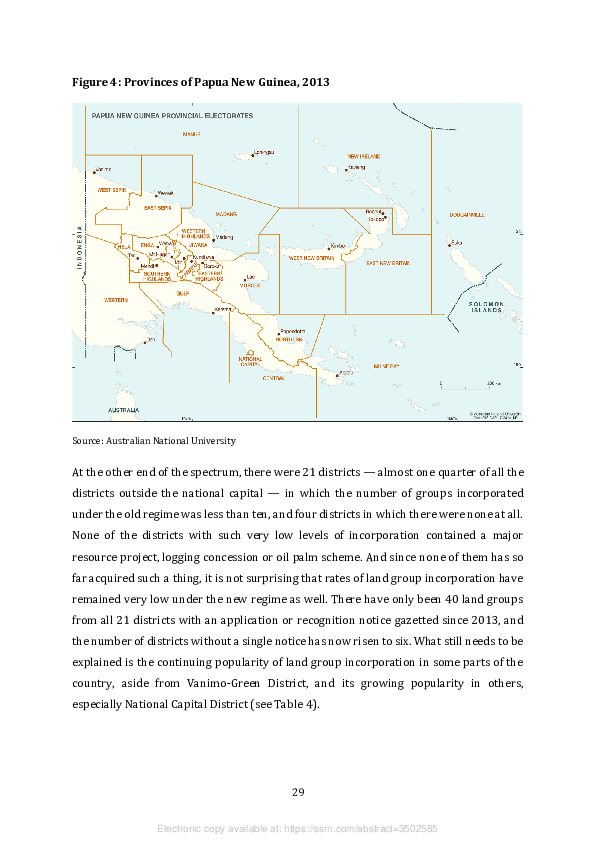

Table 2: Numbers of notices gazetted between 2013 and 2018

TYPE OF NOTICE 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 TOTAL

Application notices 36 84 116 229 420 126 1,011

Recognition notices 10 59 61 162 373 130 795

Survey notices 14 16 31 16 38 42 157

Acceptance notices 5 12 6 16 31 17 87

Land title notices 4 7 4 12 32 16 75

Source: Author’s calculations based on notices published in the PNG National Gazette

Although the Land Groups Incorporation Act of 1974 required the registrar to publish

recognition notices, this did not become standard practice until October 2011.6 The

timing of this innovation seems to be linked to the hearings of the Commission of Inquiry

into SABLs, where Lands Department officials were admonished by the commissioners

when they conceded that previous applications for incorporation had invariably been

approved because no steps had been taken to verify their authenticity. A total of 51

recognition notices were gazetted between October 2011 and the end of February 2012,

immediately before the new Act came into effect. Only two such notices were gazetted in

the remaining ten months of 2012, and another four were gazetted in November 2013,

but all six of the land groups covered by these notices were assigned numbers that

belonged to the old series, so it seems that they were not being recognised under the

terms of the new legislation. The first group to be recognised under the new legal regime

5 Two groups were wound up in light of a local land court decision dating from 2011. A third was found to

be party to a land dispute that was still subject to litigation. The fourth was found to have fabricated a

connection between two different clans from two different villages.

6 In 2018, Lands Minister Justin Tkatchenko said this was the main reason that groups incorporated

under the old regime were ‘non-genuine’ (Anon. 2018a).

17

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

was the Auwi Hembi group in Hela Province, which was assigned the new series number 1

by means of a recognition notice published in March 2013. This group’s application notice

had been published in February that year. Nine other groups got recognition notices with

numbers from the new series during the course of that year. All ten of these groups were

among the 36 that had their application notices gazetted in 2013.

The strange thing is that 60 groups generated survey notices in 2012, and another 12

generated survey notices in 2013, without having been subject to recognition notices that

assigned them a group number in the new series. The first of these was a set of survey

notices published in May 2012. They came from 57 land groups in West Sepik Province,

with a combined claim over more than 38,000 hectares of land, whose application notices

had been gazetted in 2009, well before the new legislation came into effect. Their claims

were subject to a set of acceptance notices published in September 2012, but no

corresponding set of land title notices has ever been gazetted. One of the other three

groups that were responsible for survey notices in 2012 laid claim to a single portion of

more than 72,000 hectares of land in Western Province; another claimed seven different

portions of land around the city of Lae, with a combined area of roughly 30 hectares; and

the third claimed ownership of three portions in the national capital, Port Moresby, with

a combined area of roughly 130 hectares. None of these claims has ever been subject to

an acceptance notice, although the land group in Lae eventually got a recognition notice

in June 2016, while the other two groups are still ‘unofficial’. Of the 12 groups that were

yet to be recognised when they generated survey notices in 2013, five subsequently got

acceptance notices, and six subsequently got land title notices, although one of them did

not get these notices until 2016, by which time it had been officially recognised.

There were two unofficial groups — groups without recognition notices — in West Sepik

Province that received their acceptance and land title notices on the same day in 2013,

another in Madang province that received both notices on the same day in 2014, and a

fourth in Morobe Province that received both notices on the same day in 2015. There was

also one unofficial group in the national capital that received its land title notice in 2014

without being the subject of any previous acceptance notice, let alone a recognition

notice. Of the two groups that did get a recognition notice before generating a survey

notice in 2013, one, in Western Province, was likewise able to get a land title notice

18

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

without getting a previous acceptance notice, while the other one, in the national capital,

only got an acceptance notice without getting a land title notice.

It would therefore seem that some land groups were able to proceed some way along the

path to registration of their land titles without ever being granted official recognition as

groups incorporated in compliance with the amended version of the Land Groups

Incorporation Act.

The 795 land groups that got official recognition notices between March 2013 and

December 2018 were assigned numbers that ranged from 1 to 1177. There are three

cases in which the same number was assigned to two different land groups in different

parts of the country. It is not clear why some of the numbers in the sequence have not

been assigned to any of the land groups that got recognition notices. There is evidence to

indicate that the registrar has been granting some certificates of recognition without

publishing the gazettal notices that correspond to them, but the Acting Secretary of the

Lands Department announced that only 725 certificates had been issued by September

2018 (Anon. 2018b).7 However, the gazettal notices indicate that this figure had already

been reached in June of that year, so it seems that most of the missing numbers have not

been allocated at all.

One might suppose that all of the 794 groups that had been recognised, and not officially

‘wound up’, by the end of 2018 would have had their application notices gazetted in

advance of their recognition notices. But this is not the case. While the National Gazette

tells us that 290 land groups had officially applied for recognition without being officially

recognised by the end of 2018, it also tells us that 85 groups had been officially recognised

without having their application notices gazetted beforehand.

The practice of publishing survey notices for groups that have not previously been subject

to application or recognition notices has also persisted since 2013. Of the 47 survey

notices gazetted in 2014 and 2015, 19 came from land groups that had not previously

been subject to recognition notices issued in accordance with the new legislation,

although three of them were subject to recognition notices after their survey notices had

7 Lands Minister Justin Tkatchenko is reported to have said that ‘about 2000-plus’ land groups had been

registered under the new legal regime before the end of 2018 (Anon. 2018a), but the acting secretary

probably closer to the mark.

19

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

been gazetted. These acts of omission seem to have diminished since then. Of the 96

survey notices gazetted between 2016 and 2018, only two came from groups that had not

previously got recognition notices, and both of these groups did have their applications

gazetted under the new regime.

The practice of publishing acceptance notices for land portions that have not previously

been subject to a survey notice has also persisted throughout this period. The first such

case was recorded in September 2013, when a land group in East New Britain Province

got an acceptance notice and a land title notice, both gazetted on the same day, for two

land portions with a combined area of 12,000 hectares. Not only did this group lack

survey notices for these two portions; it also lacked any prior recognition notice in the

new series, but its application notice did finally get published in April 2016, two and a

half years after its land title had apparently been registered. Another 22 of the 87

acceptance notices published since 2013 have lacked a previous survey notice, and eight

of them have been awarded to groups that have not even received a recognition notice

during that period.

The practice of publishing acceptance notices and land title notices for particular portions

of land on the same day, in the same issue of the National Gazette, has also been

commonplace. Sixty-nine of the 87 acceptance notices have thus been accompanied by an

instantaneous or simultaneous land title notice, which seems to contravene the provision

in the legislation, and in the wording of the acceptance notices themselves, that invites

any ‘aggrieved’ landowners who share a ‘common boundary’ to register their approval or

objection within 30 days of the notices being gazetted. Of the 18 acceptance notices that

did not lead to the instantaneous grant of a land title, 16 had not resulted in any land title

notice by the end of 2018. However, in the other two cases, the land title notice was

gazetted before the acceptance notice, which is almost as strange as the case in which a

land title notice was gazetted before an application notice.

Aside from the group in East New Britain, there are 12 other unofficial land groups whose

land claims have been subject to acceptance notices, and ten of these groups have secured

land title notices on the same day as their acceptance notices. There are only three groups

that have got a land title notice without receiving an acceptance notice, but all three have

at least been subject to recognition and survey notices. Yet one of these three groups,

20

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

which is based in Morobe Province, had its survey notice and its land title notice

published on the same day in 2017, and that is even more peculiar than the 69 cases in

which land title notices have been published at the same time as the acceptance notices

to which they relate.

Survey notices, acceptance notices and land title notices all specify the area of land to

which they apply, and in cases where the same portion of land has been subject to two or

three of these different notices, the area is normally the same in each of them. There are

four cases in which the area shrank between the survey notice and the land title notice,

two of them with a very substantial reduction, and three in which it grew slightly larger.

The most extreme case of shrinkage is in the size of two land parcels that were each said

to cover 564.6 hectares in the survey notices produced by the Vaga land group from

Kirakira Village in National Capital District in November 2014. When these two land

portions were subject to acceptance and land title notices in April 2017, one had been

confined to 4.79 hectares while the other had shrunk to a mere 0.74 hectares. In such

cases, I have assumed that the most recent notice contains the most accurate measure.

A total of 185 land portions made an appearance in one or more of these three types of

notice between 2013 and 2018, all but one of which was assigned an area. Four of these

land portions were said to be in excess of 100,000 hectares, which seems to be far greater

than the area that could possibly constitute the landed property of a single clan within a

single village (see Figure 3). By far the largest is an area of 529,000 hectares, supposedly

called Keram, that was assigned to the Pukpuk (‘Crocodile’) land group from Lamdo

Village in Madang Province by means of acceptance and land title notices gazetted in

2015. No village of this name can be found in the 2000 national census, but if it really is

located in the Arabaka LLG area, as proclaimed in the group’s recognition notice, then the

whole of that area, or one of equivalent size, would seem to have become the property of

a single clan. However, the scale attached to a copy of the survey plan that I obtained from

the Lands Department reveals that the area is in fact only 529 hectares, even though the

surveyor has written ‘529,000.00’ in the middle of it.

The revelation of this order-of-magnitude problem casts doubt on the real size of three

other land parcels that were assigned to three land groups in Western Province by means

of acceptance notices gazetted on the same day in 2014. These were said to cover

21

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

186,600, 180,300 and 106,900 hectares respectively. Although the three land groups had

received their recognition notices in 2013, there were no survey notices announcing their

intention to conduct land investigations, and the acceptance notices were not

accompanied by land title notices. The acceptance notices were also unlike others of their

kind because they did not assign portion numbers or survey plan numbers to the three

land parcels, but only made reference to the existence of ‘sketch plans’ that should have

been produced in advance of any land investigation. I have not tried to obtain copies of

these mysterious documents from the Lands Department, so I do not know if they exhibit

an order-of-magnitude problem in their own right, but it looks as if procedural

irregularities might explain the failure or refusal of the Director of Customary Land

Registration to register the three titles.

Even if these three cases are ignored, and the portion called Keram is reduced to its

correct size, there is still a wide range of variation in the size of the land portions specified

in the different notices (see Table 3). One or more of the 12 portions covering more than

10,000 hectares might still turn out, on closer inspection, to be 10, 100 or 1,000 times

smaller than they appear in their gazettal notices, but it should be noted that all of them

are in rural areas, half of them were said to cover less than 20,000 hectares, and the

largest to be subject to a land title notice by the end of 2018, in West New Britain

Province, covered less than 40,000 hectares.

Table 3: Size of 182 land portions over which land groups have been seeking to

register titles between 2013 and 2018

Portion size (ha) Total portions Area claimed (ha) Area titled (ha)

Less than 1 9 3 2

1 – 10 31 124 56

10 – 100 29 1,264 517

100 – 1,000 43 19,316 7,781

1,000 – 10,000 57 176,130 101,055

10,000 – 100,000 12 292,008 123,611

TOTAL 181 488,845 233,022

Source: Author’s calculations based on notices published in the PNG National Gazette

22

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

5. An elastic deadline and the shape of novelty

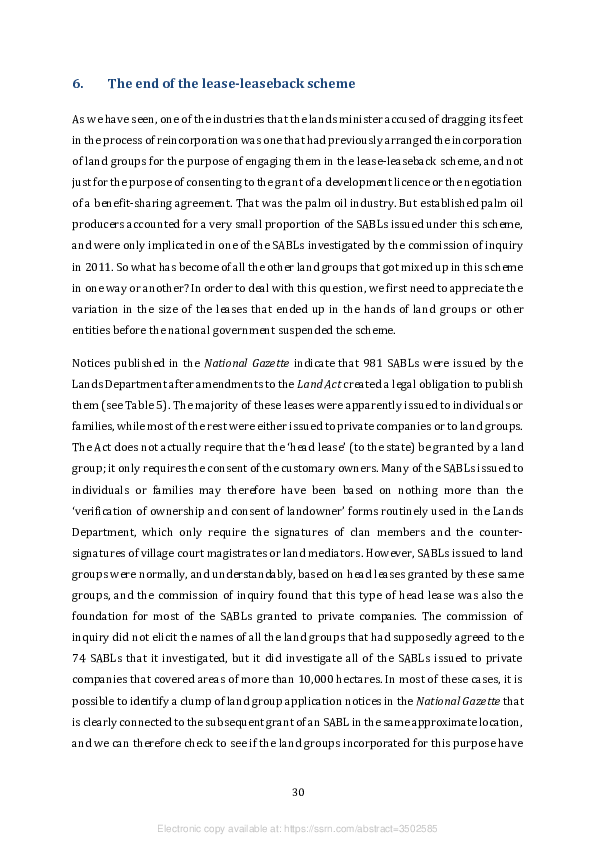

Section 36 of the amended Land Groups Incorporation Act stated that all existing land

groups had to make applications for reincorporation within five years of the Act coming

into effect, otherwise they would ‘cease to exist’. By the time this deadline expired at the

end of February 2017, 540 application notices and 316 recognition notices had been

gazetted in accordance with the terms of the new legislation, so it appeared that

thousands of land groups were on the brink of extinction. However, the registrar

suggested that the National Executive Council might save them from this fate by

extending the deadline (Tarawa 2017a), and Lands Minister Justin Tkatchenko made the

same promise later that year, explaining that ‘the extension was to avoid causing issues

with big industries including oil palm, mining and petroleum to ensure they got the

process right’ (Tarawa 2017b). Section 36 was accordingly amended in November 2018,

giving land groups incorporated under the old regime another five years to rid

themselves of what the minister called their ‘questionable (shadow) legal status’ (Kama

2018).

This invites us to consider the reasons for the difference in the spatial and temporal

distribution of the applications made under the two legal regimes, and hence the

difference between the motivations of the applicants or their corporate sponsors. Since

we already know a good deal about the links between the older groups and a range of

large-scale resource development projects in rural areas, the question is whether the

notices published in the National Gazette since 2013 reveal a similar pattern or one that

is quite different, and if it is quite different, why that should be so. Answers to this

question can only be partial, since none of these notices provides any explicit rationale

for the act of incorporation or the pursuit of a registered land title.

There has never been any systematic process of land group incorporation in the mining

sector, so there has never been a need for mining companies or the relevant government

agencies to ‘get the process right’. Compensation and royalty payments due to the

customary owners of land covered by exploration or development licences in this sector

have been made to ‘agents’ appointed under Section 9 of the Land Act. Although these

individuals may be recognised as ‘clan leaders’, the Mining Act of 1992 says nothing about

the formal incorporation of their customary groups. Less than 50 of the applications

23

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

gazetted under the old regime, and less than 20 of those gazetted under the new one,

appear to have come from people claiming customary rights over these mining

concessions. Far from encouraging such applications, company managers and

government regulators have been inclined to view them as a threat to compensation or

benefit-sharing agreements that have already been negotiated. The antics of the Piu land

group in Morobe Province are a case in point (see Section 2).

The situation is quite different in the petroleum sector, because the Oil and Gas Act

expresses a clear preference for land groups, or their executives, to be the recipients of

what the Act calls the ‘royalty benefit’ and ‘equity benefit’ that project area landowners

are entitled to receive from the development of oil and gas projects. However, the Act

does not say who should be responsible for organising their incorporation. It only says

that project proponents or developers are responsible for the conduct of ‘social mapping

and landowner identification studies’ that should help the minister to decide which

groups ought to be incorporated. The situation has been complicated by development of

the PNG LNG Project since 2010, because this project involves a combination of

‘brownfield’ licence areas, from which oil was already being exported, and ‘greenfield’

licence areas, which are new additions to the project. The project’s operator, ExxonMobil,

has never taken responsibility for the incorporation of land groups in any of these areas.

Its joint venture partner, Oil Search Ltd, has belatedly taken some responsibility for

reincorporating the Chevron groups in the brownfield licence areas because it purchased

Chevron’s stake in the oil export business in 2003, and thus inherited the files relating to

the previous incorporation of the 480 ‘Chevron groups’ (John Brooksbank, personal

communication, February 2019). The Department of Petroleum and Energy has taken

responsibility for the process of incorporation in the greenfield licence areas, but its

officers have struggled to convert the findings of social mapping and landowner

identification studies into decisions that are acceptable to a majority of local landowners

(Filer 2019). The Huli-speaking landowners in Hela Province, whose greenfield licence

areas contain most of the gas that is now being exported, have been especially recalcitrant

because they (or their representatives) object to the provision in the new legislation that

prohibits them from being members of more than one land group (Goldman 2007).

By the end of 2018, only two of the original Chevron groups had attempted to

reincorporate themselves. One came from the route of the oil export pipeline, and failed

24

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

to achieve a recognition notice. The other came from the Gobe licence area, and did

manage to achieve a recognition notice. This group, which goes by the name of Wolotou,

has been caught up in a protracted legal battle to establish its right to a proportion of the

landowner benefits derived from this area, which probably explains why its leaders want

to reaffirm its legal status. No applications for reincorporation had come from the Kutubu

licence area, which is by far the biggest of the brownfield licence areas. The only

greenfield licence area to show any significant level of activity was the ‘buffer zone’

surrounding the processing plant, just outside the national capital. Although the plant

itself was built on land that had been purchased from its ‘native’ owners back in 1906,

four nearby villages were granted some entitlement to landowner benefits. Nine land

groups from these villages had application notices gazetted between 2015 and 2018, of

which four got recognition notices, and one other group from this area got a recognition

notice without any prior application notice. This last group, called Araua, was the only

one out of the ten to have produced a survey notice, gazetted in 2018, in which it laid

claim to 54,900 hectares of land, which is more than ten times bigger than the portion of

alienated land that contains the plant site. No acceptance or land title notices have

followed this claim, so it is possible that the neighbours lodged an objection to it.

The third industry mentioned in the minister’s pronouncement has developed its own

way of producing benefit-sharing agreements with local landowners, with very little in

the way of state intervention or legal obligation. Between 1997 and 2002, the company

operating a major oil palm scheme in Milne Bay Province organised the incorporation of

33 land groups. New Britain Palm Oil Ltd, which took control of the Milne Bay scheme in

2010, had already been doing something very similar around the Hoskins scheme, in

West New Britain Province, between 1998 and 2009. In both cases, the aim of the exercise

was to extend the boundaries of the nucleus estates that were initially established on land

alienated during the colonial period by persuading local landowners to allocate some of

their customary land to ‘mini-estates’ that would be managed by the palm oil companies.

This was achieved by means of the lease-leaseback scheme. Having arranged the process

of incorporation, consultants engaged by the palm oil companies then arranged for the

land groups to lease their land to the state on condition that it then be leased back to these

same groups and then subleased to the companies, normally for a period of 40 years

(Oliver 2001; Filer 2012a).

25

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

A number of financial and institutional considerations would explain the reluctance of

company managers to revisit this process. The original process was time-consuming and

not entirely uncontentious; the legal status of SABLs was thrown into doubt by the

commission of inquiry; the validity of the leases and subleases would be called into

question if existing groups had to be divided into smaller groups in order to comply with

the new legislation; and company managers found it difficult to get relevant advice from

the Lands Department. The recommendations of the latest national land summit seem to

have justified their reluctance. Six of the land groups in West New Britain that were

probably incorporated with company support have since applied for reincorporation

under the new regime, but it is not clear how much company support has been provided

for their reincorporation.

One industry that was not mentioned in the ministerial announcement was the logging

industry. That might seem rather strange, since roughly one-third of the land groups

incorporated under the old legal regime were incorporated for the purpose of negotiating

FMAs, those agreements last for 50 years, and most of them have formed the basis for the

grant of a logging concession that is still operational. However, the Forestry Act was

designed to deny logging companies any role in the process of land group incorporation,

since that process is meant to precede the grant of a concession, and the companies now

have nothing to lose if local land groups cease to exist. Staff of the National Forest Service,

who were actively involved in the process between 1995 and 2010, have not been

directed to revisit and reincorporate as many as 3,000 groups whose chairmen are

currently in receipt of timber royalties from large-scale logging concessions. Nor would

they now have the capacity and resources to undertake such a task. Knowing this to be

the case, they advised the land group chairmen to make their own arrangements and

asked the logging companies to help them do so (Ruth Turia and Andrew Aopo, personal

communications, October 2019).

West Sepik is the only province where these communications had any obvious effect.

Between March 2017 and June 2018, 157 land groups from three LLG areas in Vanimo-

Green District, close to the Indonesian border, were listed in clumps of application notices

published in nine different issues of the National Gazette. It turns out that these groups

contained the customary owners of a selective logging concession called Amanab Blocks

1–4 and Imonda Consolidated, which covers more than 250,00 hectares of forested land

26

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

and is held by Amanab Forest Products Ltd.8 Logging company staff are known to have

facilitated the engagement of provincial forestry and lands officers in the process of

reincorporation. The odd thing is that the names of the new groups associated with this

concession bear almost no relationship to the names of the groups whose representatives

had previously signed up to the three FMAs on which it is based. The only explanation for

this discrepancy that I have been able to obtain from people involved in the latest process

of incorporation is that the first process created a large number of ‘bogus’ groups (Jim

Silu and Jack Desse, personal communications, October 2019). It is also conceivable that

land groups or ‘clans’ in this part of the country have very unstable identities, so the

current groups may turn out to be no more durable than their predecessors.

It is not clear why land group chairmen and logging company managers in other FMA

areas have failed to act on the advice provided by officers of the National Forest Service,

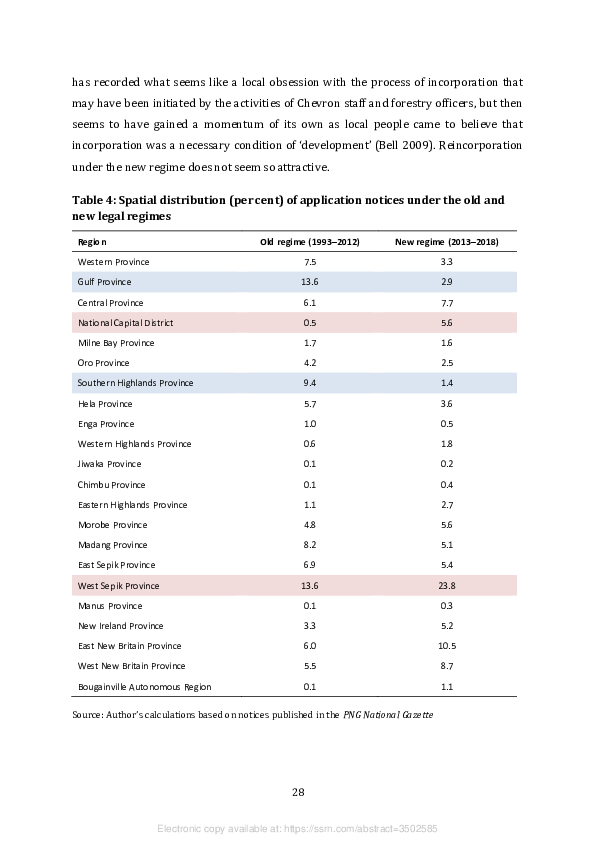

but the action taken in this part of West Sepik Province largely explains why this one

province accounts for almost one quarter of all the applications gazetted under the new

regime (see Table 4 and Figure 4). At the same time, the failure to reincorporate groups

formerly registered with the assistance of Chevron staff or forestry officers in other parts

of the country also serves to explain much of the change in the distribution of land groups

between provinces under the two legal regimes, especially the marked decline in the

proportion of groups incorporated in Gulf and Southern Highlands provinces.

The disparities are even greater at the district level. More than 80 per cent of the newly

incorporated groups in West Sepik Province are based in Vanimo-Green District, while

two of the other three districts in this province account for less than 4 per cent. In Kikori

District, one of two districts in Gulf Province, more than 1,600 land groups were

incorporated between 1993 and 2012, but only 11 applied for incorporation between

2013 and 2018, and six of these were new groups staking claims over land that might be

required for PNG’s second gas project. If all the customary landowners of Kikori District

had joined one and only one land group under the old regime, which is rather unlikely,

then 2000 census data suggest that each one would have contained only 24 members —

men, women and children. Indeed, an anthropologist working in that part of the country

8 This company is a subsidiary of the Malaysian conglomerate WTK Realty, which has been based in

Vanimo for more than 40 years and has operated a number of other logging concessions in West Sepik

Province.

27

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502585

has recorded what seems like a local obsession with the process of incorporation that

may have been initiated by the activities of Chevron staff and forestry officers, but then

seems to have gained a momentum of its own as local people came to believe that

incorporation was a necessary condition of ‘development’ (Bell 2009). Reincorporation

under the new regime does not seem so attractive.

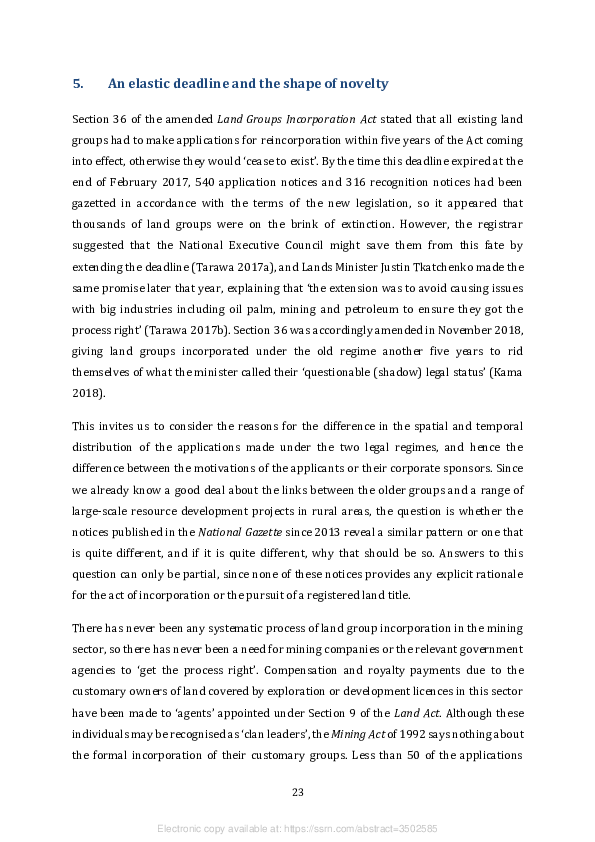

Table 4: Spatial distribution (per cent) of application notices under the old and

new legal regimes

Region Old regime (1993–2012) New regime (2013–2018)

Western Province 7.5 3.3

Gulf Province 13.6 2.9

Central Province 6.1 7.7

National Capital District 0.5 5.6

Milne Bay Province 1.7 1.6

Oro Province 4.2 2.5

Southern Highlands Province 9.4 1.4

Hela Province 5.7 3.6

Enga Province 1.0 0.5

Western Highlands Province 0.6 1.8

Jiwaka Province 0.1 0.2

Chimbu Province 0.1 0.4

Eastern Highlands Province 1.1 2.7

Morobe Province 4.8 5.6

Madang Province 8.2 5.1

East Sepik Province 6.9 5.4

West Sepik Province 13.6 23.8

Manus Province 0.1 0.3

New Ireland Province 3.3 5.2

East New Britain Province 6.0 10.5

West New Britain Province 5.5 8.7

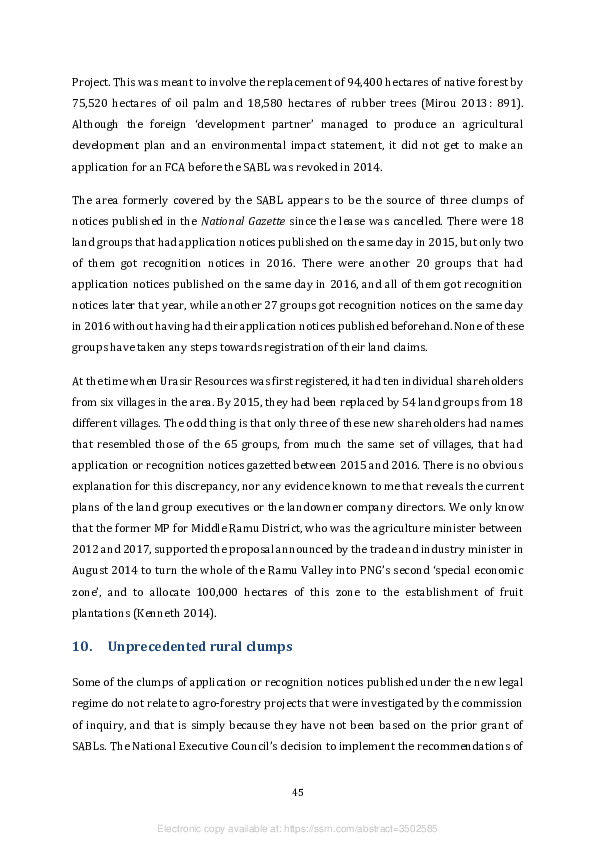

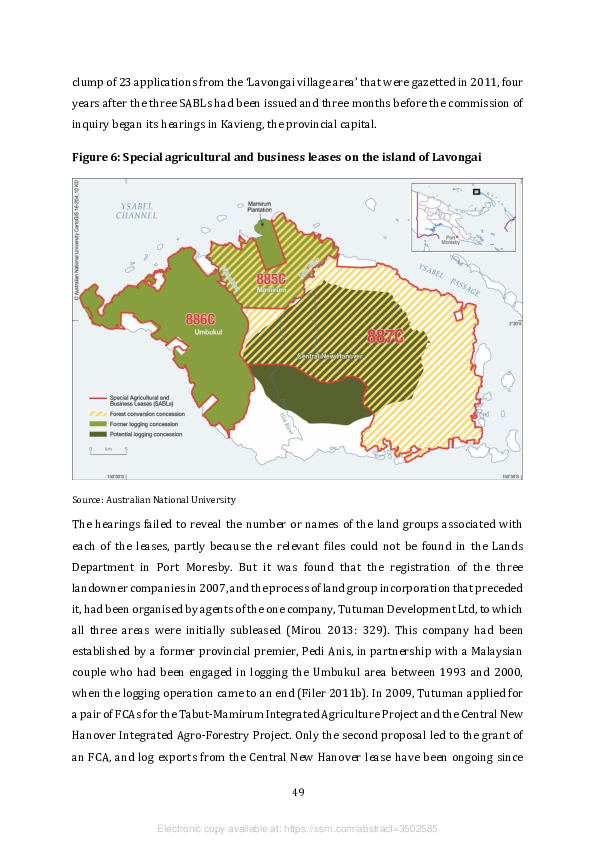

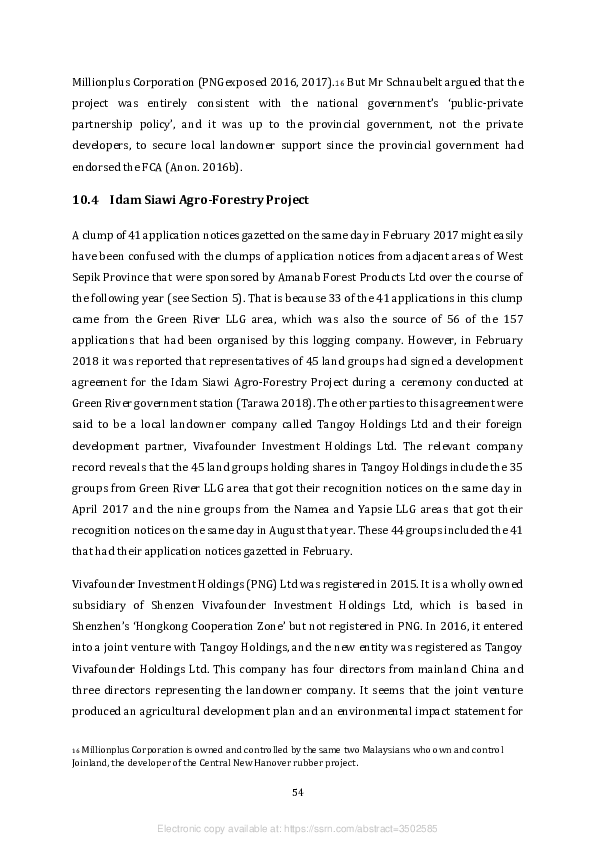

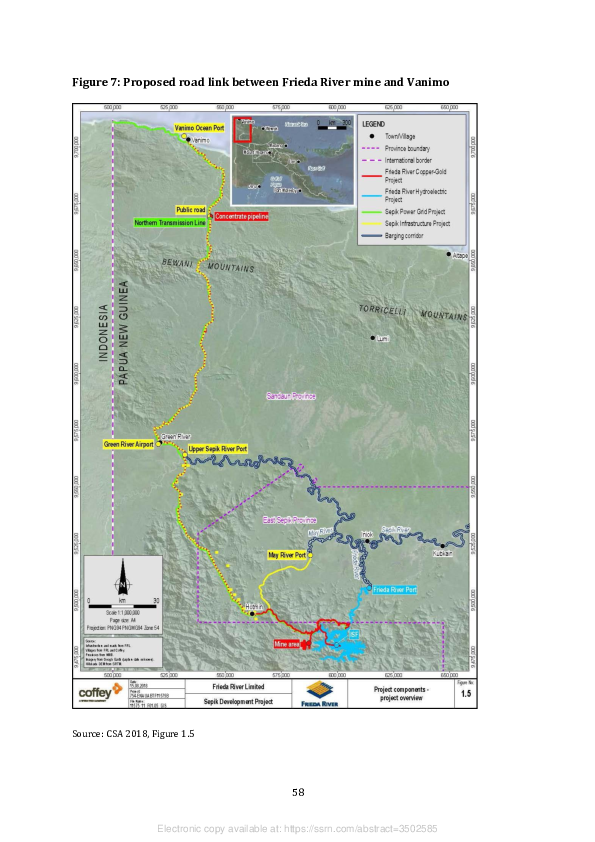

Bougainville Autonomous Region 0.1 1.1